Following the tip of World Struggle II, Servais enrolled into the wonderful artwork program at Royal Academy of Wonderful Arts (KASK) in Ghent. He spent most of his twenties as a struggling artist, taking no matter work he might discover to help his spouse and two kids. He labored odd jobs – from dishwasher to longshoreman to manufacturing unit employee to graphic designer – whereas persevering with to develop his expertise as a painter and wonderful artist. He was amongst six painters employed to color an outsized mural designed by Belgian surrealist René Magritte, and although Magritte fired Servais after an argument over technical points, they later reconciled and Servais was allowed to complete the job.

He tried his hand at producing live-action shorts and experimental movies throughout this era. Animation was at the back of his thoughts too, however the lack of technical assets and know-how prevented him from finishing animated movies. Regardless of a number of makes an attempt to supply animation, Servais didn’t end his first skilled animated movie, Harbor Lights (1960), till the age of 32.

In 1963, Servais was invited to arrange an animation college at his alma mater, KASK. On the time, no animation faculties existed in mainland Europe, and the one method to be taught the craft was via a studio apprenticeship. “We are able to say that in Europe, it was completely disconcerting to enter a studio,” he recalled. “What occurred in there was nearly ‘high secret.’” At one level, whereas nonetheless attempting to be taught animation, Servais had pretended to be a journalist and visited a number of firms, together with Ray Goossens’ studio in Antwerp and Paul Grimault’s studio in Paris, in order that he might see how the movies have been made, however his undercover makes an attempt by no means received him any nearer to understanding animation manufacturing.

Servais would oversee KASK’s program for many years afterward. The college ensured that future animation filmmakers wouldn’t wrestle for tools, information, and assets as Servais had. College students might now be taught the fundamentals of animation in mere months, slightly than the years it had taken Servais – they usually wouldn’t should pose as journalists to accumulate the data.

One in all his college students at KASK within the Nineteen Seventies was Paul Demeyer, who has since gone on to direct Rugrats in Paris and episodes of Duckman and The Rocketeer. Demeyer who would grow to be a good friend of Servais, remembered him as a instructor:

He was very systematic, one thing I later acknowledged as his method of working. We college students have been slightly intimidated by his presence. He was fairly formal, not essentially in his look, which was all the time a blue denims swimsuit and a bit hat, however in his calm demeanor and his mirrored method of talking. Balanced and comfy, all the time attentive and current, nearly like a monk. He was not the sort of instructor who joked round, or tried to be appreciated by the scholars, he was simply himself.

Servais hit a stride within the Nineteen Sixties, and between 1963 and 1973, he directed eight animated shorts, together with Chromophobia (1965), a deceptively cheerful-looking allegory a couple of fascist regime that sucks the colour out of society, and Operation X-70 (1971), which he created as a response to seeing photographs of the American navy gassing the Vietnamese. “I made a decision to supply a parody of the struggle,” says Servais of the latter movie. “It was my method of expressing my horror, of protesting in opposition to the violence.” Servais’ movies have been effectively obtained at worldwide festivals, profitable dozens of awards, together with first prize on the Venice Movie Competition (Chromophobia) and a particular jury prize at Cannes (Operation X-70).

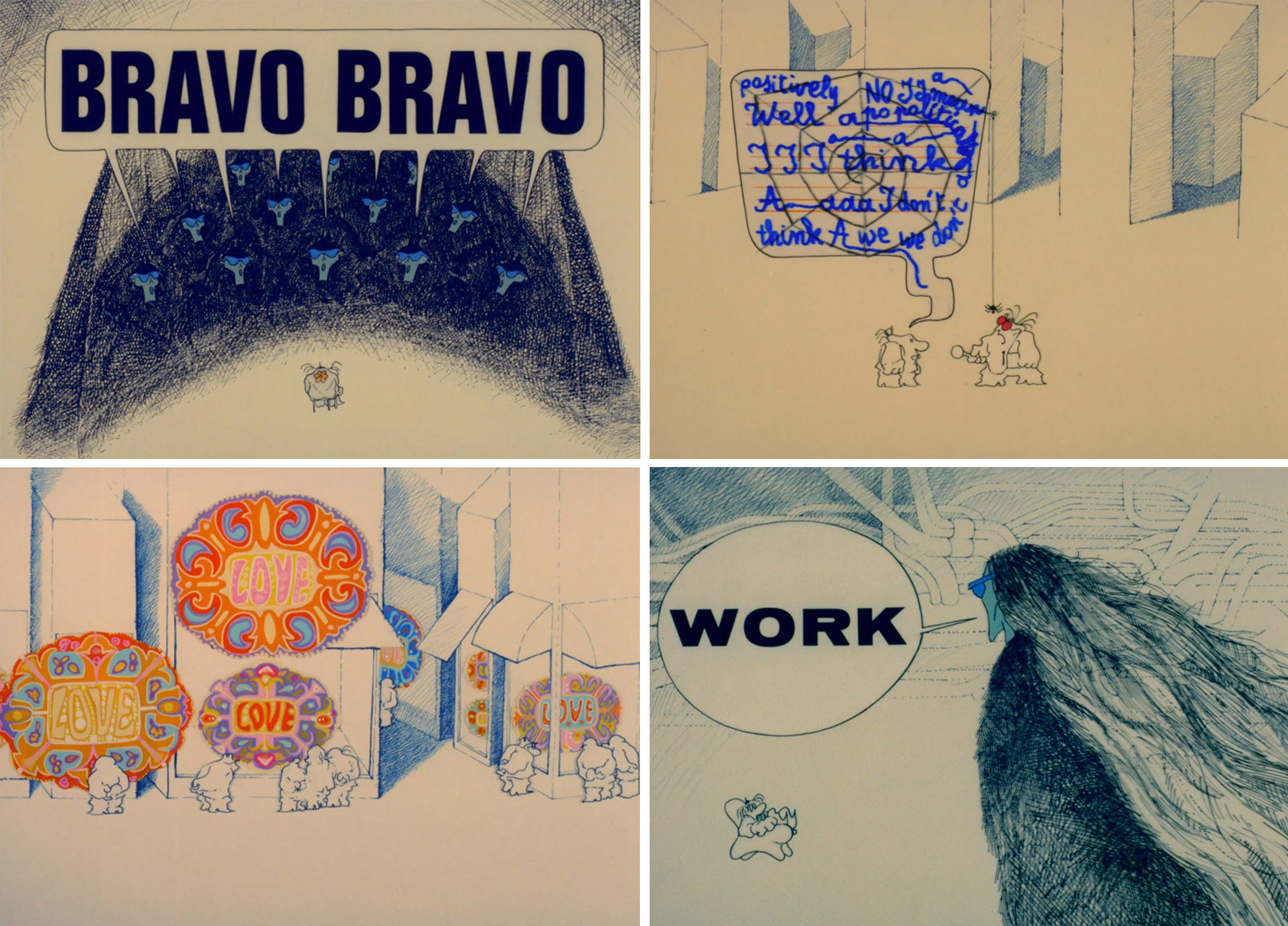

Servais was all the time in dialog with modern tradition and artwork round him. Goldframe (1969) is a satire of Hollywood hubris, whereas To Communicate or To not Communicate makes use of comedian speech bubbles and Pop Artwork parts in its exploration of, in Servais’ phrases, “the manipulation of the person, which exists in an aggressively capitalist world of cash in addition to in a fascist, militaristic world.”

One other movie, Pegasus (1973), about man’s worry of being changed by expertise, references Flemish expressionists comparable to Fixed Permeke, Gustave De Smet, and Frits Van den Berghe. Servais stated that utilizing these artists as inspiration was a straightforward selection: “I couldn’t comprehend why folks have been so eager on imitating Hollywood. Why not use our personal graphic custom, our personal character?”

The numerous graphic kinds and visible methods that Servais employed in his movies led one movie critic to look at, “Let’s imagine that each movie by Servais is just not solely an anti-Disney movie, but in addition an anti-Servais movie, in as far as he refuses to repeat itself.” Nowhere is that this more true than Harpya (1979), a standout instance of animated horror that makes use of a hybrid strategy of stay actors mixed with optical and animated results. The movie was a exceptional success, incomes Servais the Cannes Palme d’Or for brief movie and cementing his fame as a serious pressure in European animation.

One filmmaker who was impressed by Harpya was future Pixar artistic chief John Lasseter. He recounted a narrative to me whereas I used to be writing The Artwork of Pixar Quick Movies that came about within the mid-Eighties. Lasseter was presenting animation assessments of a Luxo lamp at an animation competition in Belgium. Servais, who was in attendance, requested him afterward in regards to the movie’s story. Lasseter stated that the movie didn’t have a narrative; it was only a character examine. The reply left Servais unhappy, and he informed Lasseter {that a} piece of animation, regardless of how temporary, will need to have a narrative with a starting, center, and finish.

Whereas Servais’ personal work might be ambiguous and open to interpretation, his remark to Lasseter informed of his personal method to filmmaking. Servais’ movies won’t have adopted the traditional narrative beats of Hollywood (which, by the way, is probably going why he was by no means nominated for an Oscar), however he however positioned a robust worth in storytelling and speaking with audiences via his paintings. Lasseter took Servais’ recommendation too and developed these animation assessments into Luxo Jr. (1986), the enduring two-minute movie that will function a calling card for the fledgling Pixar.

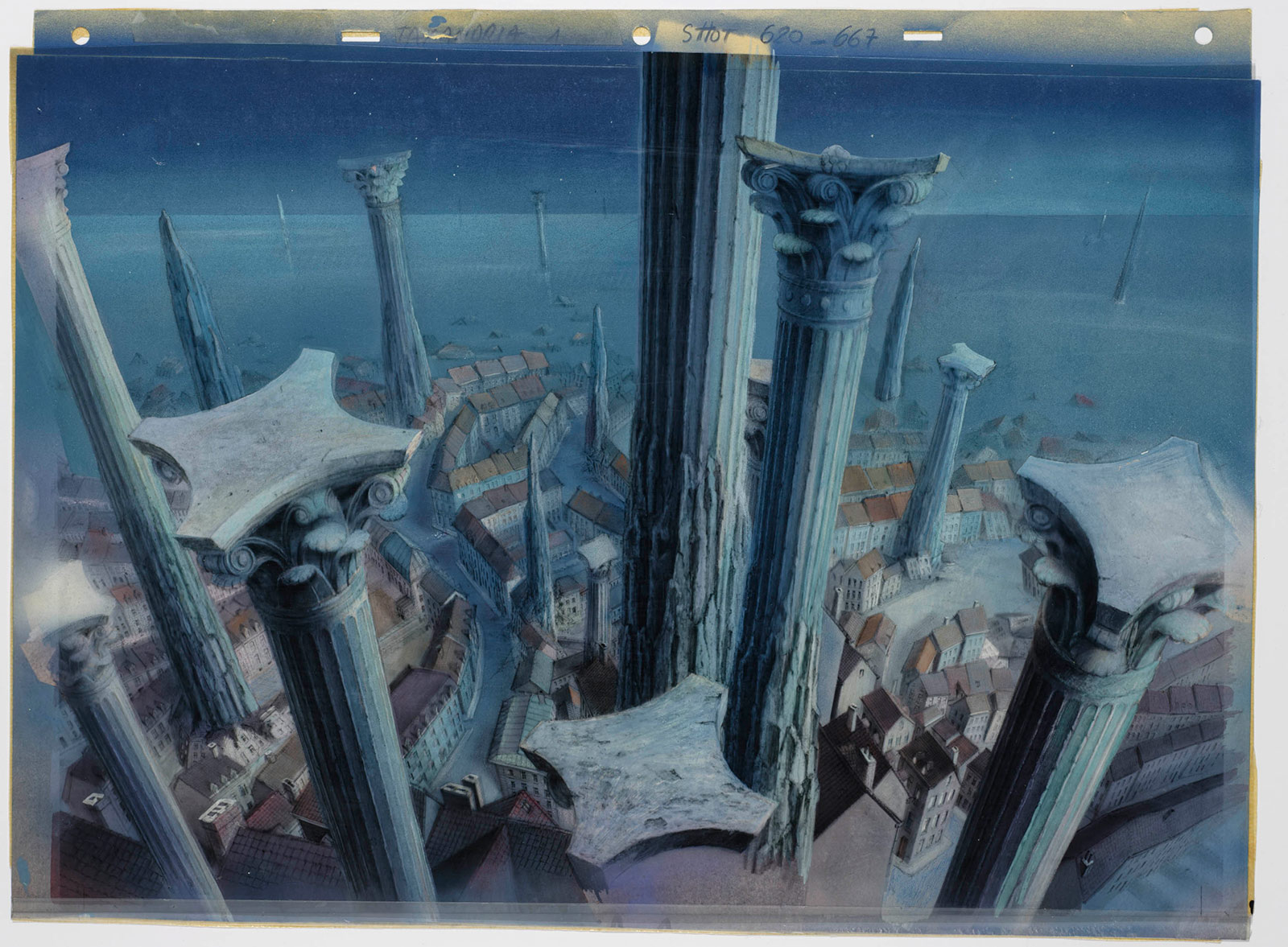

Following Harpya, Servais didn’t launch one other movie for 15 years. When he did, he stunned everybody with the feature-length Taxandria (1994), a fantasy a couple of totalitarian regime that has banned the idea of time. An bold however flawed movie, the years-long manufacturing and post-production didn’t go as he’d envisioned. He battled with producers over the movie’s script, which was reworked repeatedly by totally different writers, and he might by no means persuade the monetary backers to totally embrace his imaginative and prescient for a hybrid movie, so the movie ended up being largely stay motion. Though the expertise was a private and monetary disappointment for Servais, the movie holds an attention-grabbing spot in his oeuvre as the one long-form work he created, whereas additionally being notable for its use of early digital compositing methods. Simultaneous to the manufacturing of the movie, Servais additionally served because the president of ASIFA, the Worldwide Animated Movie Affiliation, between 1986 and 1994.

Servais returned to type in 1998 with Nocturnal Butterflies, a brief movie that was a tribute to Belgian surrealist painter Paul Delvaux and which earned Servais his first grand prix at Annecy. The hybrid movie was made utilizing a patented approach known as Servaisgraphy that he had initially developed for Taxandria and which made it potential to mix stay actors with animation methods. With the advances in digital compositing although, the laborious Servaisgraphy approach was by no means used past this movie.

Servais continued to make movies till the tip of his life . His final movie, The Tall Man, was launched in 2021. In later years, Servais was the recipient of numerous honors and exhibitions devoted to his movies. A significant 2021 retrospective in Belgium, entitled “Raoul Servais: Between Magic and Realism,” has made its catalog out there totally free HERE and it accommodates detailed details about Servais’ life and work for anybody involved in studying extra about him.

François Schuiten, the Belgian illustrator who curated “Between Magic and Realism” and was additionally a key artistic collaborator on Taxandria, mirrored not too long ago on the qualities that make Servais’ work timeless:

The truth that he by no means made any concessions. His work is extraordinarily pure, true to the intentions and convictions of its maker. Raoul doesn’t do no matter it takes to please. He approaches the whole lot with meticulousness and rigor. His creations are sober: no a part of them is unintended, the whole lot has which means. And the idea of time in his oeuvre is in contrast to another. Time in Raoul’s movies typically stands nonetheless, is infinite, or lasts for all eternity. Taxandria existed exterior of time solely. Raoul stored reinventing that movie, re-editing it again and again, till I might now not see the movie itself – solely all of the totally different movies he’d woven into it over time.