by Jeremy Clarke.

Chie Hayakawa‘s dystopian drama Plan 75 examines a few of the social fallout of a authorities coverage whereby Japanese folks can voluntarily have themselves terminated after age 75.

Sedate classical piano music performs on the soundtrack. The out of focus picture might be wanting down a hall. After a protracted wait, a person in a T-shirt and denims walks, in focus, into image foreground. There seems to be blood on his arm and he’s carrying a shotgun. Forward of him, because it now comes into focus, the hall flooring is sparsely scattered with objects: a cup and a bowl, an outdated particular person’s strolling stick to 4 legs, one thing else which we will’t fairly make out. He washes on the sink. One other hall – a fallen strolling stick, a pair of slippers, an deserted bathrobe or maybe a towel, a collapsed, half-folded wheelchair, wheel nonetheless spinning. T-shirt and denims with shotgun descends the steps. After a contentious voice-over, T-shirt and denims waits a protracted whereas, then factors the barrel of the shotgun at his head and makes use of his toes to tug the set off.

A contentious, heartfelt, male voice-over says: “The excess of seniors is draining Japan’s financial system and taking a heavy toll on the younger era. Absolutely the aged don’t want to be a blight on our lives. The Japanese have a protracted historical past of sacrificing themselves to profit the nation. I pray that my sacrificial act will set off dialogue and a future that’s brighter for this nation.”

Leaving apart the truth that all this might have been achieved on display screen with way more precision and financial system in round a 3rd of the time – one thing which by the way might be mentioned of the entire two-hour movie, which bulks out Hayakawa’s authentic 2018 wanting the identical identify, made as a part of the Ten Years: Japan anthology – this so-called ‘sacrificial act’ means not a lot an act of sacrifice, however an act by which the perpetrator sacrifices not solely himself but in addition a sufferer or victims. We by no means discover out any extra about both, this scene is presumably speculated to resonate with a bit of stories introduced over the TV or radio: right now the federal government handed the Plan 75 invoice, giving the appropriate for assisted suicide to all residents aged 75 and over. Hate crimes in opposition to the aged are talked about. (Ah, so that’s what’s been happening.) This unprecedented resolution to Japan’s ageing inhabitants downside has captured the world’s consideration.

This new, live-action function is a far cry from Katsuhiro Otomo’s script for the anime Roujin Z (1991) which likewise tackled the issue of a rising aged inhabitants, however with way more financial system, even when its fetishisation of a fairly, younger feminine nurse seems distinctly dodgy right now. Roujin Z posited a machine that might deal with an outdated particular person’s each bodily and psychological want, thereby eradicating from the youthful era any accountability of caring for his or her elders. However Haruko, the nurse on the centre of the story, flies within the face of this perspective: a superb one that needs to do the appropriate factor by any affected person in her care. When she will get an aged, hospitalised hacker to enter the persona of her affected person’s late spouse into his caring machine, it goes on the rampage in an try to take “her husband” to the seashore.

Plan 75, by means of distinction, is a stay motion, dystopian drama by which the dystopia seems just about like current day Japan, however with the Plan 75 invoice enshrined in legislation. The scene-setting opening bloodbath however, it follows three foremost characters whose paths will ultimately cross. One among 4 aged ladies working as resort chambermaids is Michi (Weathering with You‘s Chieko Baisho), curiously not named till the 4 of them are involuntarily retired from work a way into the movie; they quickly get collectively to check notes and take a look at Plan 75 brochures.

Michi’s daughter hasn’t saved in touch, so the outdated woman has by no means seen her grandchildren. She retains in contact along with her finest buddy from work, fellow former chambermaid Ineko (Hisako Okata), till someday she visits the latter and finds her lifeless of pure causes. From this level on, Michi is actually alone.

Discovering employment at age 78 proves a near-insurmountable downside. Finally, all she will get is evening shifts directing visitors, which appears extremely unsuitable work for somebody that age.

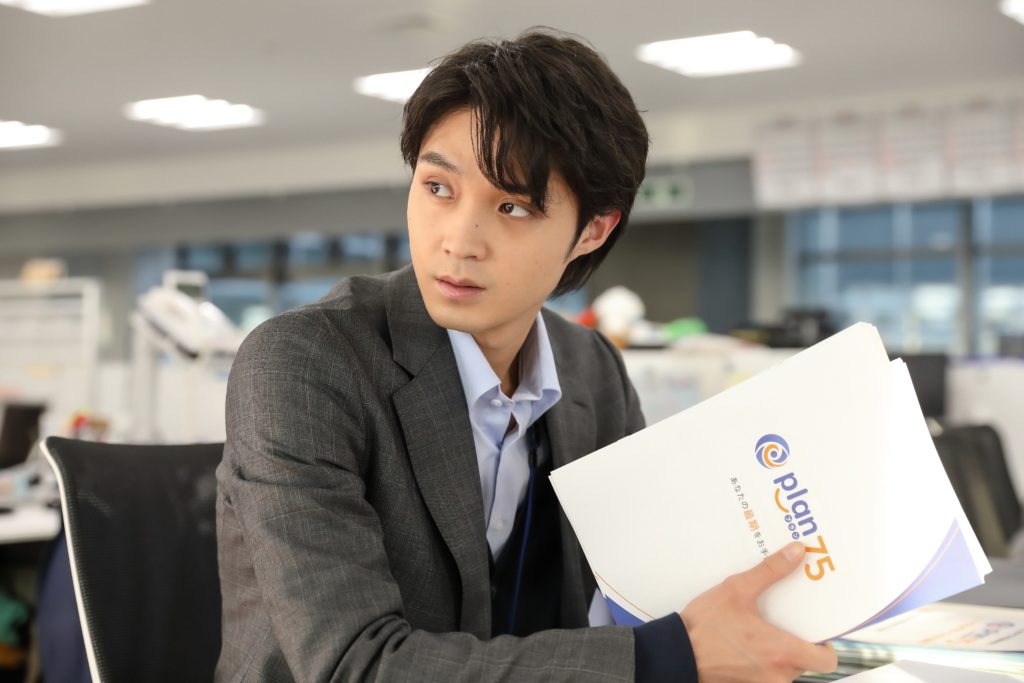

With nothing left to stay for, ending her life appears pretty much as good an possibility as any. Signing up for Plan 75 comes with a $1 000 money bonus (the English subtitles use {dollars} quite than yen) which she doesn’t know what to do with. You are able to do what you want with it, she’s advised when initially interviewed by useful Plan 75 worker Hiromu (Hayato Isomura).

Such encounters as carried out within the movie are very Japanese: folks attempting exhausting to be well mannered to and please each other and being terribly apologetic. On this occasion, that hides the truth that the State is principally asking outdated folks to kill themselves, and outdated folks, maybe out of a need to not be a burden on the youthful era or the broader Japanese society, are going together with it. (That is very totally different from Roujin Z, the place a small group of outdated males are fixated on intercourse and unattainable younger nurses, and react to the federal government programme of robotic carers by one among their quantity enthusiastically hacking into one such robotic to render way more humane its pre-programmed agenda to take care of its outdated aged shopper).

Hiromu is the narrative’s second main character. He later finds himself interviewing the uncle he’s not seen for 20 years and who did not attend Hiromu’s father’s funeral. Plan 75 has protocols in place for such issues, and the uncle is transferred to one among Hiromu’s co-workers. The guilt-ridden Hiromu nonetheless makes an attempt to get to know his uncle higher, visiting him at residence and finally driving him to the power the place, within the subsequent cubicle over from Michi, he’s to voluntarily terminate his life.

In a uncommon, really touching second inside a movie the place for essentially the most half every little thing takes a ridiculously drawn out period of time to occur, Michi lies on the termination facility mattress with medication being distributed via a respiratory equipment. The younger nurse attending her has a telephone dialog about, “perhaps it’s damaged down – I’ll come over there now.” All of a sudden, Michi is alone and anxious. On her proper, within the subsequent cubicle, she sees Hiromu’s uncle (who she’s by no means seen earlier than) additionally receiving the drugs via a masks. Maybe there may need been a connection there, however it’s too late for both of them now. Or so it appears. The set-up inadvertently recollects one of many tales in Kenshi Hirokane’s manga Capturing Stars within the Twilight, by which two outdated folks volunteering for euthanasia as an alternative strike up a last-minute friendship.

The third main character is a Filipino Christian working in Japan whereas her household stays again within the Philippines. She is going through monetary hardship on account of the approaching hospital operation her five-year-old daughter wants. A buddy at her home church places her on to a extra profitable job working for Plan 75, eradicating private results from corpses. Her male co-worker reveals her surprising advantages: the lifeless don’t take something with them, and all their objects go to landfill, so she may as nicely take something she finds that she likes. This might embody cash, if the corpses have it on their particular person. For instance, we see him taking a pair of outdated spectacles higher than those he presently wears, and placing his outdated ones within the tray of the deceased’s possessions. She grapples briefly with the morality of this – we will see it going via her thoughts – is it a type of stealing? – however swiftly realises he’s proper and adapts to the thought.

In direction of the tip, she is on her shift when a distraught Hiromu turns up hoping he’s to not too late to avoid wasting his uncle, so she involves his assist.

One minor character is value a point out. Michi is assigned Plan 75 telephone operative Yoko Narimiya (Yumi Kawai) within the run-up to her voluntary termination, with whom she will get a paltry quarter-hour per name. Michi pours out her coronary heart to Yoko, who breaks protocol by agreeing to fulfill along with her. It’s okay so long as no-one finds out, says Yoko, and on this occasion no-one ever does. Michi voluntarily offers Yoko a few of her $1 000 money grant since she doesn’t know what else to do with it. On their closing telephone name, Michi pours out her coronary heart to Yoko in gratitude for every little thing she has completed for her, just for Yoko to present a terse, bureaucratic, scripted farewell that breaks Michi’s coronary heart in a matter of seconds.

Alongside Yoko, we later overhear a bunch of newly recruited Plan 75 staff being advised that the aim of their telephone calls is to assist their purchasers undergo with the termination, quite than pulling out as they’re legally allowed to at any level – a chilling if totally plausible revelation.

Regardless of such occasional flashes of brilliance, Plan 75 shouldn’t be a fantastic movie. It walks via quite than will get to grips with the problem of voluntary euthanasia – for that, you’d be higher off seeing final 12 months’s French drama Every little thing Went Superb. It’s not likely provocative sci-fi coping with the issue of the social burden of an ageing inhabitants like Roujin Z or (though it offers with different issues too) Hollywood’s Soylent Inexperienced (1973). Nonetheless, it does present a terrifying glimpse right into a Japanese view of that challenge which means that it may not be one of the best nation on the planet by which to develop outdated and die.

Plan 75 is launched within the UK and Eire on twelfth Might 2023.

Jeremy Clarke’s web site is jeremycprocessing.com